by Fereidoon Sioshansi, PhD, Menlo Energy Economics

One of the critical issues facing the assembled delegates at the COP28 (lead article) was the fate of fossil fuels in the immediate, short- and longer-term. Everyone recognizes that we cannot realistically transition away from our current fossil fuel dependence – around 80% – overnight. And nearly everyone – except the fossil fuel industry and its supporters – agree that we eventually must if the aim is to address climate change. The question is how soon and how fast. Unsurprisingly, the views are widely divided on this.

The fossil fuel industry, whose views were reflected at the recent climate summit and elsewhere (box below), want to prolong the status quo for as long as possible, that is to continue with additional investments and increased production while delaying any penalties or restrictions on emitting vast quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. They don’t want to pay for their own direct emissions, the so-called scope 1 emissions, nor for much larger emissions when their products are used by customers, the scope 3 emissions.

This allows them to prolong a highly profitable business while ignoring the significant externalities associated with the production and use of their products. They can continue to make obscene profits and reward their shareholders and CEOs while inflicting irreversible damage on the environment and future generations. Cigarette manufacturers did – and continue to – inflict serious damage to smokers whose medical bills are paid by others, the taxpayers and insurance companies.

What they want us to believe is that life without fossil fuels is unpleasant if not impossible, so we must put up with the consequences. They have known about the adverse impacts of their business for decades – long before many scientists – and decided not to reveal their findings and deny them even when the scientific community came up with irrefutable evidence.

When push comes to shove, they point to (meagre) investments they have made in renewables and green technologies as evidence of their good intentions. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) the fossil fuel sector invested about 2.5% of its capital in clean energy in 2022 and said that the share should rise to 50% by 2030 to align with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. How likely is that?

Oil and gas companies currently account for a mere1% of global clean energy investment – and 60% of that comes from just 4 companies.

When pushed further their favorite response is carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) and/or direct air capture (DAC). But the technology to capture carbon from the power plant stack or soak it up from the atmosphere in scale that would make a significant dent does not currently exist nor appears to be imminent, certainly not at a reasonable cost.

According to a 25 Nov 2023 special report in The Economist, Climateworks, one company engaged in the field estimates the cost to remove a tonne of CO2 at $600, not cheap.

Carbon Engineering, another company engaged in the same field reckons it might cost in the range of $90-230 but the article notes that “… there is no indication that such costs have yet been achieved.” Moreover, these range of numbers are orders of magnitude more than what cap and trade carbon markets currently pay for carbon removal (see below).

Trust us. We’re the good guys

Speaking at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in San Francisco in mid-Nov 2023 Darren Woods, ExxonMobil’s CEO, expressed his frustration with global climate mitigation efforts while reassuring the audience that big oil is actually the good guys.

"Oil and gas companies reliably provide affordable products essential to modern life. Making them into villains is easy. But it does nothing — absolutely nothing — to accomplish the goal of reducing emissions." Exxon, the biggest listed oil major – Saudi Aramco is much bigger but is only partially listed – has been under pressure since a 2016 revelation that the company knew about the connection between fossil fuels and climate change as early as 1977 but decided to ignore the evidence while allegedly undermining the scientific evidence in subsequent years.

As Woods sees it "reducing supply" – as suggested by the IEA – is “hogwash.”

“We cannot replace overnight an energy system that took 150 years to build.”

If the aim is to "get real" about net zero, then governments should invest taxpayers’ money – not Exxon’s – into things such as carbon capture and sequestration (CCS). “That’s how we can finally get to the bottom of this environmental disaster,” he said. Exxon’s preferred solution is like arguing that cigarette companies are not responsible for causing health issues and governments should focus on remedies like chemotherapy. As for what Exxon knew and why it did not share it, Woods said he is personally "more interested in what Exxon knows today," which is, "Climate change is real," and "Human activity plays a major role."

This may not sound earthshaking, but for many years Exxon would not subscribe to either statement. Woods assured the San Francisco audience a month prior to COP28, "We've got the tools, the skills, the size — and the intellectual and financial resources — to bend the curve on emissions. That's what Exxon knows."

He, however, did not elaborate how he would use these formidable assets to address climate change.

The Economist highlights a few of the inherent challenges starting with the fact that removing carbon from the air, or DAC, is like looking for the proverbial needle in an enormous haystack. Given current carbon concentration in the 417 parts per million range, it represents 0,04% or one part in 2400. This requires pushing massive volumes of air through a system that requires lots of chemicals and energy to capture the carbon.

How much is carbon removal worth?

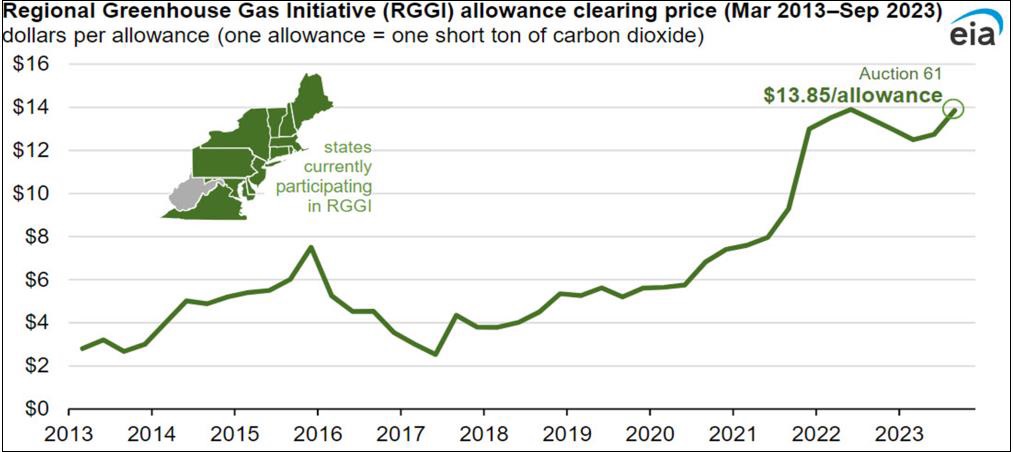

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) was established in 2009 as a cooperative effort among 12 eastern states – Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia – to reduce CO2 emissions from power plants. RGGI reduces the number of allowances available in auctions over time to reduce regional emissions and adjusts the total to take into account unused allowances from earlier auctions, exerting upward pressure on prices. Proceeds totaled $304 million in the September 2023 auction and have totaled $6,7 billion since inception. Participating entities can trade allowances on secondary markets. The latest auction resulted in a clearing price of $13,85 per ton for CO2 emission allowances (Figure 1). The number is orders of magnitude lower than the cost of CCS, suggesting that it is best to reduce emissions at the source rather than try to remove it once it has been emitted. As everyone knows, an ounce of prevention is far cheaper than a pound of cure.

Another study by Oxford University’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment also concluded that placing undue faith in CSS is not prudent since it would cost at least $30 trillion more over the next 30 years than an alternative strategy focused on accelerating the rapid deployment of renewables and electrification. According to the Oxford report,

“The cost of CCS implementation has not declined at all in 40 years, in contrast to renewable technologies like solar, wind, and batteries, which have fallen in cost dramatically.”

Even more damning is the following:

“Any hopes that the cost of CCS will decline in a similar way to renewable technologies like solar and batteries appear misplaced. Our findings indicate a lack of technological learning in any part of the process, from CO2 capture to burial, even though all elements of the chain have been in use for decades”.

The fossil fuel industry’s favorite solution, in other words, is not remotely economical now or in the foreseeable future. As your editor sees it, the less carbon emitted the better because there is no guarantee that we can take it out in scale and at reasonable cost any time soon.

Fatih Birol, the IEA’s Ex, Dir calls CCS and DAC an illusion and points to the total implausibility of capturing large amounts of carbon as a practical solution. Your editor is reminded of the small child who noticed that the emperor did not have any clothes in the Hans Christian Andersen’s famous fairy tale The Emperor’s New Clothes.

The alternative narrative, which the fossil fuel industry does not want you to hear, may be found in the IEA’s report The Oil and Gas Industry in Net Zero Transitions released prior to the COP28 summit. In rather blunt language it says,

“Oil and gas producers around the world need to make profound decisions about their future place in the global energy sector. The industry needs to commit to genuinely helping the world meet its energy needs and climate goals – which means letting go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution.”

Moreover, the IEA report sets out what the global oil and gas sector needs to do to align their operations with the goals of the Paris Agreement. It says that the $800 billion currently invested annually in the sector is double what is required in 2030 on a pathway that limits warming to 1.5 °C.

The IEA points out that the oil and gas industry invested around $20 billion in clean energy in 2022, or roughly 2.5% of its total capital spending and says this must rise to 50% by 2030.

In short, the IEA is unequivocal: the pathway to net zero by 2050 requires the oil and gas industry to shrink and shrink substantially. It says that those players who survive the shrinkage – presumably the lowest cost producers with the lowest carbon footprint – will have to spend multiples more on clean energy than they currently do.

Clearly, there are two distinct and disjointed narratives on the future role of fossil fuels. A quote, attributed to Theodore Roosevelt – repeated from the Dec 2023 issue – says that when confronted with making an important decision, “… the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing.”

Concerned citizens, investors and policy makers must choose the right narrative and do the right thing because – left on its own – the fossil fuel industry will not.

Acknowledgment

This article was first published by Eenergy Informer and is republished here with permission.