This is a summary of a new report into the ongoing devastating heath impacts caused by air pollution from Eskom’s coal-fired power stations

The results of a recent study undertaken by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) serve to remind us that the burning of coal for the generation of electricity in South Africa causes the premature death of thousands of people every year. It also increases the number of people suffering from serious respiratory diseases. This, despite the country having implemented a minimum air quality standard (MES) in 2010.

The report, Health impacts of Eskomʼs non-compliance with minimum emissions standards, reveals that the massive amounts of toxic gases and deadly particulates emitted by Eskom’s power stations pose a massive health risk to all South Africans, especially children.

By allowing Eskom to continue operating its coal fired power stations without the prerequisite pollution mitigating equipment for so long, the government has permitted a situation where the country’s state-owned power utility is now the world’s worst emitter of SO2.

Under Eskomʼs planned retirement schedule and emission control retrofits, emissions from the utilityʼs power plants would be responsible for a projected 79 500 air pollution-related deaths from 2025 until end-of-life.

Full compliance with the MES at all plants that are scheduled to operate beyond 2030 would avoid a projected 2300 deaths per year from air pollution and economic costs of R42 billion per year, starting from 2025.

Eskomʼs retrofit plan only realizes one quarter of the health benefits associated with compliance with the MES, due to the almost complete failure to address SO2 emissions. On a cumulative basis until the end-of-life of the power plants, compliance would avoid a projected 34 400 deaths from air pollution and economic costs of R620 billion.

Other avoided health impacts would include 140 000 asthma-related visits to hospital emergency rooms, 5900 new cases of asthma in children, 57 000 preterm births, 35 million days of work absence, and 50 000 years lived with disability.

If the compliance deadline was delayed to 2030 instead of 2025, compliance with the emission limits would still avoid a projected 26 400 deaths from air pollution and economic costs of R470 billion. Requiring the application of best available control technology at all plants, instead of the current MES, by 2030, would avoid 57 000 deaths from air pollution and economic costs of R1000 billion compared to the Eskom plan.

South Africaʼs Minimum Emissions Standards (MES) for combustion installations were issued in 2010, with a phased introduction where existing sources had to meet a more lenient set of standards by 2015 and a more stringent set of standards by 2020. Most importantly, these standards would require, for the first time, coal-burning facilities to install sulphur dioxide emissions controls.

After the issuance of the standards, South Africaʼs largest emitter Eskom failed to initiate the required planning and implementation of the emission control retrofits, and government authorities failed to monitor Eskomʼs actions, leading to an impossible situation where there was no more enough time to retrofit the fleet. Because of this, Eskom was granted postponements to the standards until 2025.

For plants planned to retire by 2030, compliance with the standards was suspended. While the postponements were time-limited, Eskom made it clear that it did not intend to comply even after the deadlines ran out. In 2020, the emission limit for SO2 was further weakened from 500 to 1000 mg/Nm3, potentially enabling the standards to be met using emission technology with lower investment costs.

Compliance with the MES, even after the weakening, would result in major reductions in air pollutant emissions. However, in comparison to best international practice, the MES are highly lenient. For example, the European Union now requires old coal-fired power plants to limit SO2 in flue gases to an annual average of 95 mg/Nm3, less than one tenth of the limit value in South Africa.

As a result of the failure to act on its SO2 emissions, Eskom has become the largest power sector emitter of SO2 in the world. Other major emitters, particularly Chinese utilities, have carried out major retrofit programs and successfully reduced their SO2 emissions.

Emissions

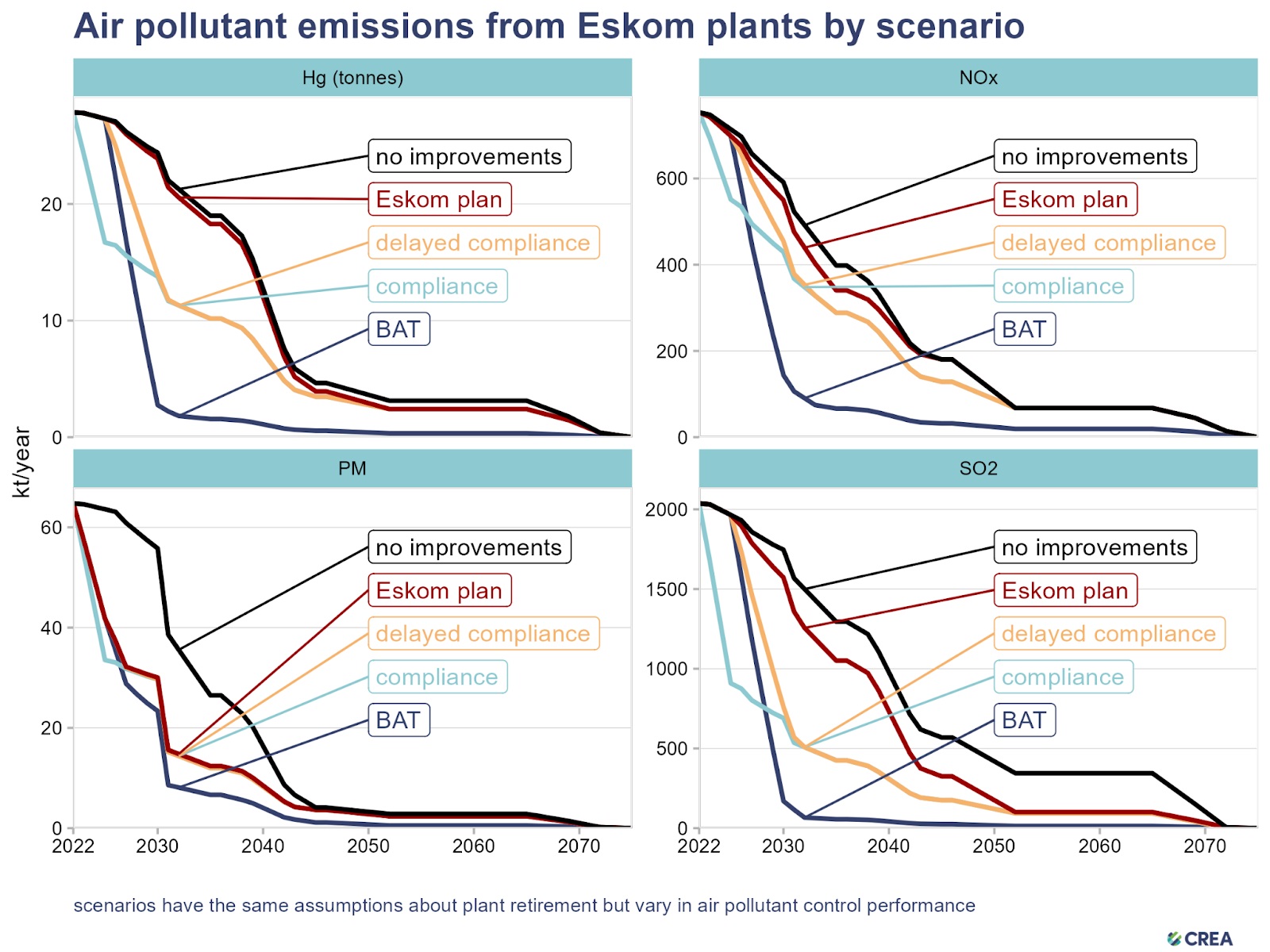

The report projects emissions, air quality impacts and the resulting health and economic impacts of air pollution from Eskomʼs coal power plant fleet under four different scenarios of compliance with the MES (see Figure 1).

- Compliance scenario: assumes that Eskom meets its legal obligations and complies with the MES by 2025 at all stations that have not received a suspension.

- Delayed compliance scenario: assumes that it takes until 2030 to achieve compliance.

- Eskom plan scenario: Eskomʼs proposed plant retrofits which see all plants except Medupi and Kusile operate until end-of-life in breach of the emissions limits, particularly for SO2.

- Best available technology (BAT) scenario: assumes that compliance with the MES is delayed until 2030, but the emission limits are tightened to align with best international practice.

Full compliance with the MES would reduce Eskomʼs emissions of SO2 by 60%, PM by 50%, NOx by 20% and mercury (Hg) by 40%, compared with a scenario of no improvements in emission control technology.

Mercury is not regulated under the MES, but compliance would significantly affect the emissions of this toxic pollutant regardless, as the installation of SO2 controls captures mercury from the flue gases as a side benefit. Eskomʼs proposed retrofit plan would bring the fleet into compliance with the MES for PM and realize the associated emissions reductions by 2030, five years after the deadline.

However, the plan would only reduce SO2 by 13%, NOx by 11% and Hg by 3%, compared with a scenario of no improvements in emission control technology. The small reductions in SO2 emissions are the main concern, as SO2 is the pollutant with by far the largest health impacts from Eskomʼs power plants, due to the formation of secondary PM2.5.

Economic impact of air pollution

Air pollution both increases the risk of developing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and increases complications and deaths from them, significantly lowering the quality of life and economic productivity of people affected and increasing healthcare costs. Economic losses as a result of air pollution are based on labour market data and pay particular attention to applicability in middle- and low-income countries.

The Global Burden of Disease project has quantified the degree of disability caused by each disease into a “disability weight” that can be used to compare the costs of different illnesses. The economic cost of disability and reduced quality of life caused by these diseases and disabilities are assessed based on disability weights, combined with the economic valuation of disability used by the UK environmental regulator DEFRA and adjusted by GNI PPP for South Africa.

The deaths of young children are valued at twice the valuation of adult deaths, following the recommendations in OECD (2012). The valuation of future health impacts is based on the premise that the long-term social discount rate is equal to long-term GDP growth rate, and the economic loss associated with different health impacts is proportional to the GDP, resulting in a constant present value of health impacts over time.